Last night Affirm filed to go public, herding yet another unicorn into the end-of-year IPO corral. The consumer installment lending service joins DoorDash and Airbnb in filing recently, as a number of highly-valued, venture-backed private companies look to float while the public markets are more interested in growth than profits.

TechCrunch took an initial dive into Affirm’s numbers yesterday, so if you need a broad overview, please head here.

This morning we’re going deeper into the company’s economics, profitability and the impact of COVID-19 on its business. The last element of our investigation involves Peloton and the historical examples of Twilio and Fastly, so it should be fun.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money. Read it every morning on Extra Crunch, or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Affirm is a company that TechCrunch has long tracked. I was assigned an interview with founder Max Levchin at Disrupt 2014, giving me a reason to pay extra attention to the company over the last six years. This S-1 has been a long time coming.

But is Affirm another pandemic-fueled company going public on the back of a COVID-19 bump, or are its business prospects more durable?

But is Affirm another pandemic-fueled company going public on the back of a COVID-19 bump, or are its business prospects more durable?

Let’s get into the numbers.

Economics

First, let’s discuss Affirm’s core economics. I want to know three things:

- What does Affirm’s loss rate on consumer loans look like?

- Are its gross margins improving?

- What does the unicorn have to say about contribution profit from its loans business?

These are related questions, as we’ll see.

Starting with loss rates, Affirm thinks it is getting smarter over time, writing in its S-1 that its “expertise in sourcing, aggregating, protecting, and analyzing data” provides it with a “core competitive advantage.” Or, more simply, Affirm writes that it has “data advantages that compound over time.”

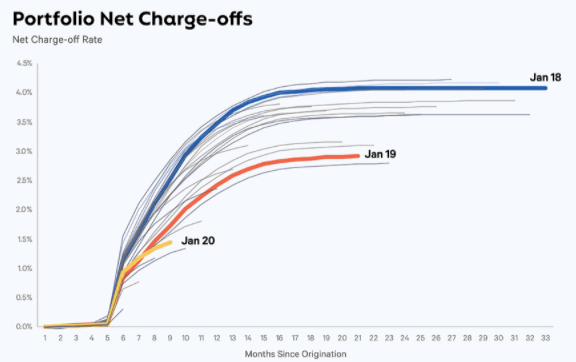

So we should see improving loss rates, yeah? And we do. The company has a very pretty chart up top in its IPO filing that makes its model’s improvement appear staggeringly good over time:

But, things aren’t improving as fast inside its results, as Affirm later explains when discussing its aggregate, as opposed to cohort-delineated, results.

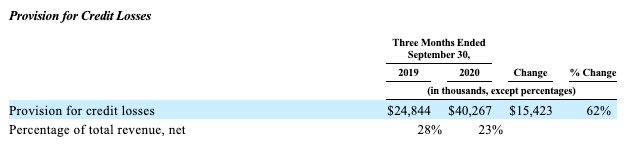

Here’s Affirm discussing its provision for credit losses in its most recent quarter (calendar Q3 2020) and the period’s year-ago analog (calendar Q3 2019):

As we can see, the percentage of total revenue that Affirm has to provision for expected credit losses is going down over time. That’s what you’d hope to see.

To better explain what’s going on, let’s explore what Affirm means by “provision for credit losses.” Affirm defines the metric as “the amount of expense required to maintain the allowance of credit losses on our balance sheet which represents management’s estimate of future losses,” which is “determined by the change in estimates for future losses and the net charge offs incurred in the period.”

And it got quite a lot better in the last year, which the company says was “driven by lower credit losses and improved credit quality of the portfolio.” So, Affirm is getting better at lending as time goes along. What does that mean for its gross margins?

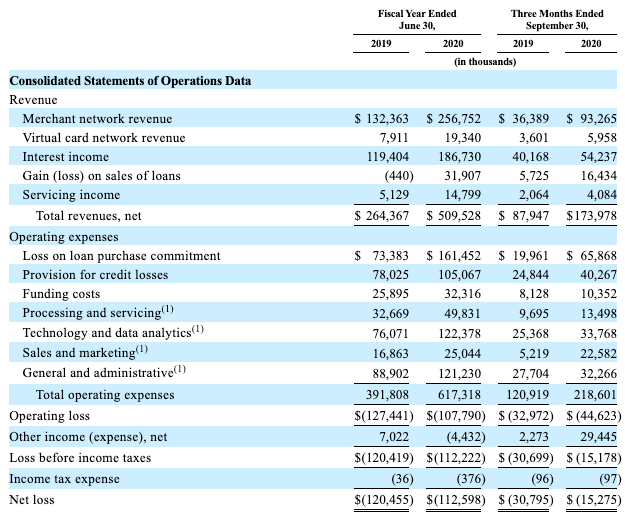

Well, Affirm doesn’t provide direct gross margin results. So we’re left to do the work ourselves. For reference, this is the income statement we’re working off of:

Fun, right? Annoying, but fun.

How should we calculate the company’s gross margins? We can’t drill down on a per-product basis given that costs aren’t apportioned in a manner that would allow us to, so we’ll have to take Affirm’s revenue as a bloc, and its costs as a bloc as well.

https://ift.tt/3hBN9RE Inside Affirm’s IPO filing: a look at its economics, profits and revenue concentration https://ift.tt/2UF4oXR

0 comments

Post a Comment